Social media is not just about cute animal memes and pictures from stunning vacation destinations. There’s a darker side to these platforms that, from a mental health perspective, can make them nothing short of a minefield.

Young people and children, whose brains are still developing, can be especially vulnerable to mental health issues such as anxiety, depression and body image issues — issues that may be worsened or even caused by social media.

Who bears the responsibility for mitigating these risks? From a legal standpoint, the answer remains unclear.

In January 2023, the Seattle Public Schools became the first school district in the nation to file a lawsuit against several social media companies to hold them accountable for the “harm caused to students’ social, emotional and mental health.” Since then, more than 50 school districts have joined the suit, and other schools and districts around the country have filed suits of their own.

For a team of researchers at the University of Washington Bothell, these cases sparked a new line of research, which they summarize in their recently published article, “Mental Health v. Social Media: How U.S. pretrial filings against social media platforms frame and leverage evidence for claims of youth mental health harms.”

Mental health v. social media

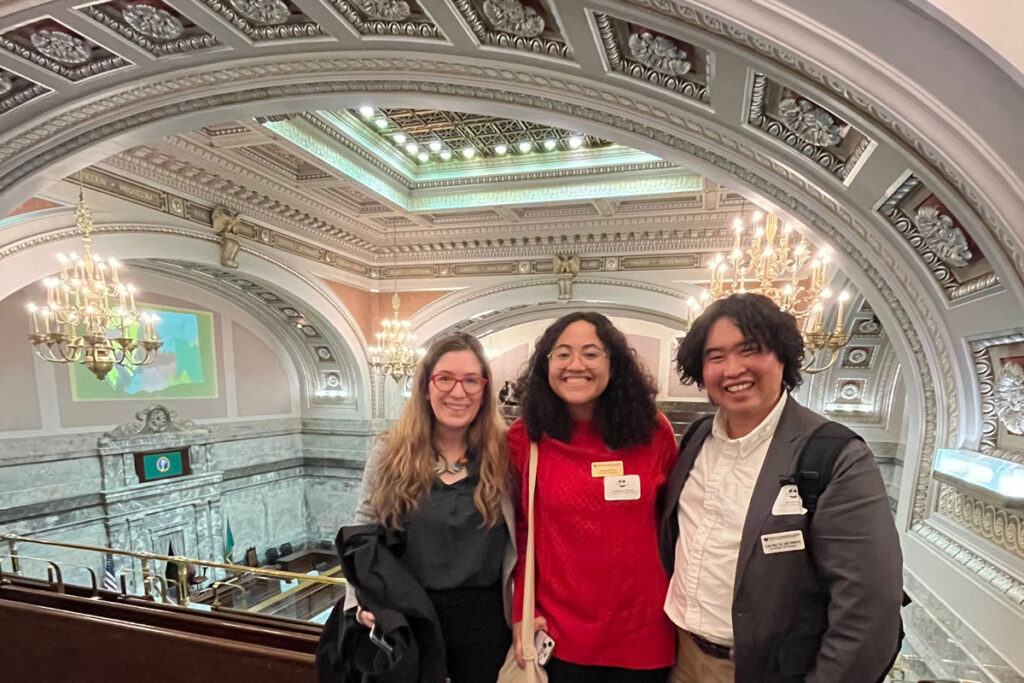

Dr. Nora Kenworthy, a professor in UW Bothell’s School of Nursing & Health Studies, has long been interested in how technology intersects with health — both where it can be used for good, and where it may be causing harm. As a public-school parent, she said the social media lawsuits were significant on both personal and scholarly reasons.

She enlisted one of her students, Jacqueline Richards, a graduate student majoring in Community Health & Social Justice, to be her co-researcher. She then helped Richards prepare the research for publication.

For Richards, this project was her first time serving as the primary author in a research publication. “I was very excited by this project. Professor Kenworthy was so generous in helping me through this process and providing helpful feedback.

“I love research and doing work in this arena of mental health and technology use is really important to me,” Richards added, noting that she had previously been a peer counselor in high school and double majored in Psychology and in Public Health as an undergraduate at the University of California Berkley.

To provide mental health expertise, Kenworthy also invited Dr. Kosuke “Ko” Niitsu, SNHS assistant professor and psychiatric mental health nurse practitioner, to join the team.

“I work at the Counseling Center here at UW Bothell, and many of my clients are college students who are young adults so I find this research into social media particularly important,” Niitsu said. “This project has inspired me a lot as well.”

The burden of proof

The research team’s objective was to gain a better understanding of what research was being used in the pre-trial filings and whether it provided causality — as well as what additional research might help make a case for mental health impacts.

“The first question was really, how can we as researchers do better to generate research that might be useful in these processes?” Kenworthy said. “We know that the way you identify and define a problem often leads to specific policy outcomes. This seemed like an important social moment, and we were interested in how that was being framed.”

The harmful effects of social media are widespread — from low self-esteem stemming from the “Keeping Up With the Kardashians” phenomenon of comparing oneself to others, to the dangers of having one’s interests pushed to unhealthy extremes by algorithms. As these platforms are also often overrun with misinformation, Niitsu said, they can even chip away at a person’s ability to trust people or information at all.

While many of the negative mental health impacts of social media are well known, proving population-level causality remains the biggest challenge in holding these platforms accountable, Kenworthy said. “It’s sort of like studying other health harming industries — except way harder.

“As an industry that has impacts on health, one comparison might be the tobacco industry, but if everyone smoked,” she said. “If everyone in the world was smoking, how do we measure who is being harmed by it and how much? If all of us are living at least some segment of our lives online, then how do we measure things like exposure? Is it the amount of time you spend online? The platforms you use? The type of content and how you interact with it?”

A community-based approach

In their paper, the team concluded that the legally cited research on social media health harms lacks strong causal evidence. They also noted that the lawsuits often overlooked existing research on disproportionate impacts to marginalized groups.

Further research in this area could not only help determine causality, Kenworthy said, but also help provide answers about how best to mitigate the impacts.

“It’s going to be really hard to establish population-level causality, but as a more qualitative researcher what I’m most interested in is the community-based, youth-driven research that identifies what people’s concerns are and helps them understand how to live in better relationship with technology,” Kenworthy said. “That’s where I think it’s worth putting our effort.”

Added Richards, “So much of the conversation has been about regulating youth and what youth are doing wrong on the internet. It feels like we’re punishing youth,” she said. “Adults also have mental health problems when it comes to interacting with social media, so it seems like the issue is not just about youth development but a wider-spread problem that needs to be focused back on how the platforms are creating algorithms that are addictive or harmful and spreading content that isn’t healthy.”

From a clinical standpoint, doing more objective research on the specific mental health impacts could also better support these cases, Niitsu said. “For example, if we say social media tends to impact attention span, that’s something researchers can actually measure.”

“What I’m most interested in is the community-based, youth-driven research that identifies what people’s concerns are and helps them understand how to live in better relationship with technology.”

Dr. Nora Kenworthy, professor, School of Nursing & Health Studies

Living with technology

Despite the harm social media can cause, it’s necessary to remember that social media has positive impacts and that these platforms still provides value for many users, Niitsu said.

“Social media can help us connect with each other and provide community where there otherwise wouldn’t be.”

Kenworthy also noted that users can try to limit negative impacts of social media on their mental health. “As someone who both researches this and tries to be thoughtful about how I am online, I am increasingly aware of how impossible the choices are for where we engage — and how pulling back or exiting from social media platforms that don’t feel good to us can often be difficult,” she said. “My plea would be for everyone to be kind to themselves.

“Most of all, I hope that we will continue to find ways to support each other ‘IRL,’ not just mediated by platforms.”

Already, Kenworthy and Richards have begun work on their next research project, which examines how people with chronic illnesses and disabilities use digital technologies as a form of care. Richards said she then hopes to work in a research institute after she graduates in June.