There is one lake in Washington where Arctic grayling still survive. And despite the pandemic and restricted operations for the University of Washington, a team led by UW Bothell Teaching Professor Jeff Jensen has continued its research on this precarious fish through the summer of 2020.

The researchers found conditions at the lake had changed significantly from the previous year, yet the fish were adjusting.

Jensen is building on research started by David A. Beauchamp in the 1980s when he was a UW graduate student and Jensen was an undergraduate. This population of Arctic grayling was thought to rely on a single snow-fed stream for spawning. By following up on Beauchamp’s work, Jensen suspected he might find indications of climate change.

The Arctic grayling is a freshwater member of the salmon family about the size of a trout. In the 1940s, state fisheries workers planted the fish in a few North Cascades lakes for anglers, who also caught cutthroat trout. The grayling were able to reproduce only at Upper Granite Lake. Jensen’s research documents the environment on which the grayling depend, including water temperature and streamflow from melting snow.

Adventures in field work

The lake in the Mount Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest is about 6 miles off Highway 20 near Marblemount. It’s a challenging hike up an abandoned logging road and across terrain without an established trail. In summer 2019, Jensen made two hikes to the lake with Prieuer Pretorius, a senior who graduated from UW Bothell in 2020 in Biology.

In summer 2020, Jensen made five (actually four-and-a-half) hikes to the lake, accompanied at times by Anders Wennstig, a senior majoring in Conservation & Restoration Science; recent graduates Quinn Moldestad (Biology ’18), Isabel Rodriguez (Biology ’20) and Alex Wachter (Earth System Science ’20); and Bellingham hiker Pete Horst, who heard about the project and volunteered to help pack gear.

Because of the coronavirus pandemic, everyone had to travel in their own car, stay in their own tent and maintain a physical distance on the hikes and at the lake, Jensen said.

What was the half-trip? On their first attempt in mid-June, they were blocked by a big creek about a third of the way in to the lake. They returned four days later with a 20-foot ladder, which was just long enough for them to bridge the creek.

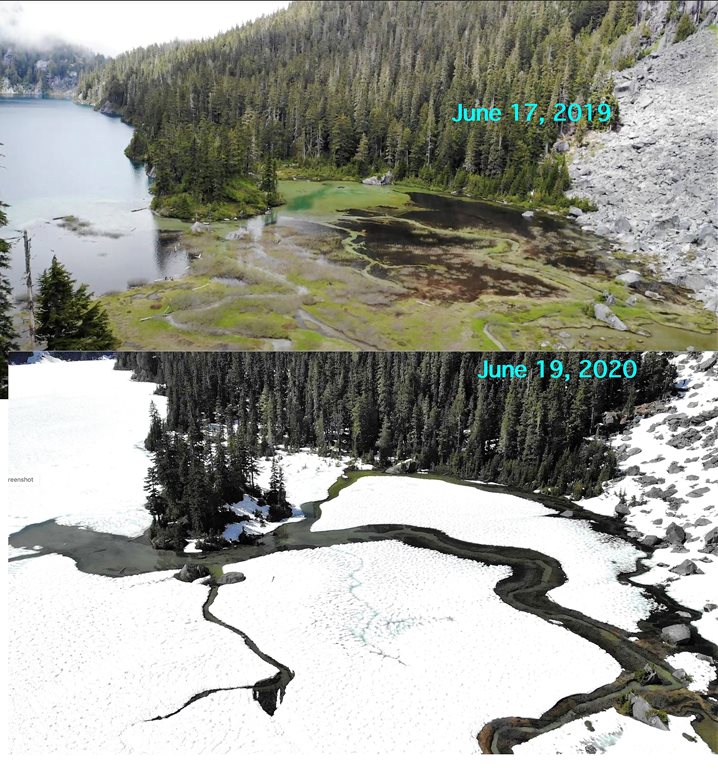

Finally reaching Upper Granite Lake, the researchers found it was still frozen over, Jensen said, but they were able to take some video from a drone and drop temperature monitors in a slice of open water.

Spawning surprise

When they returned on the third hike around July 10 and a fourth hike on July 25, Jensen was surprised by what they found. The grayling were spawning, but the stream the fish had used in 2019 was partially blocked and had a low flow. Instead, they were using a second stream that had been thought to be unsuitable because of silt. They also were spawning at the outlet at the other end of the lake where they weren’t expected.

“They can move to the other stream when they need to and use spawning areas that weren’t previously used,” Jensen said. “It looks like they have more flexibility than we thought.”

Beauchamp, now with the U.S. Geological Survey at the Western Fisheries Research Center in Seattle, remains interested in the UW Bothell research.

“The re-routing of flow and response by the grayling and cutthroat trout is fascinating!” Beauchamp enthused in an email to Jensen.

By the fifth and final trip in mid-August, the snowmelt had run off, and Upper Granite Lake had dropped 2 feet since the first measurement of the summer, Jensen said. The spawning run was over. There were no grayling in the streams.

A few could still be seen in the lake shallows, Jensen said, noting he could catch them by fly fishing. At that time of the year, there are enormous numbers of mosquitoes for the fish to feed on, which made the hike nearly unbearable for the researchers.

A continuing story

What Jensen found particularly interesting this year was the contrast with 2019, when the lake and spawning stream were consistent with what Beauchamp had reported in the 1980s. Why the big difference?

“My take is that it’s hard to pick out the signature of climate change because there’s so much variation from year to year,” Jensen said, adding that he’s looking ahead to what he’ll find in summer 2021.

“Even though we know the grayling were able to spawn in a different stream, we don’t yet know whether the eggs and fry survived as well as in the original stream.”

Students interested in undergraduate research are welcome to join Jensen — if they feel up to the hike — and add to the record of Arctic grayling in Upper Granite Lake and what that may signal.

“I think it’s really important for biology students to get field experience,” said Jensen, who teaches both Salmon in Society and Introduction to Biology in the School of STEM. “In addition to the intrinsic interest in this, it’s a nice opportunity for students who might be going into wildlife biology or fisheries biology. You get a chance to get out in the field, collect data and see things outside the lab and off campus.”