The war between Israel and Palestine. U.S. gun violence and mass murders. Disinformation and misinformation. The U.S. presidential election. Supreme Court rulings.

Events in 2024 created so much dissension and controversy — and society became so fractured — that leaders at the University of Washington decide to create a class to help students navigate the strife.

Offered in autumn quarter, “2024: Dialogue, Disagreement and Democracy” was an asynchronous online class with an urgent mission: Teach undergraduates how to talk across differences without “cancelling” each other.

Dr. Cinnamon Hillyard, associate vice chancellor for Student Success and associate professor in the School of Interdisciplinary Arts & Sciences, led the 44-strong UW Bothell cohort of this tri-campus offering. Citing a recent UW survey that shows widespread public distrust in higher education, she framed the class as a way to better serve the entire state — not just people who are liberal leaning.

“It’s personally important for me that we create spaces so everybody who comes to UW Bothell feels safe to share what they’re thinking,” she said. “We need to understand where people are coming from, or we’re not serving them.”

Role models for global citizens

“2024: Dialogue, Disagreement and Democracy” was the first time a tri-campus class format had been offered since 2020. Each week, 198 students from the Bothell, Seattle and Tacoma campuses watched videos featuring authors, legislators and other leaders discussing hot-button topics and how to approach them. Then the students offered their own reflections in a virtual gathering space.

Dr. Ed Taylor, the UW’s vice provost and dean of Undergraduate Academic Affairs, conducted eight separate video interviews in which he modeled the civility and close listening skills that students would later practice in person.

“These are global conversations. They’re not local conversations,” said Taylor in one of the videos. “They move and transcend our respective campuses and ask us to be in conversation with citizens across the world.”

After watching the weekly videos, students shared individual reflections with their assigned instructor. Halfway through the quarter, the format shifted to a discussion board visible to the entire class — no matter the students’ home campus.

“We spend so much time on our individual campuses,” said Caeden Statia, a UW Bothell junior. “It’s difficult to appreciate the others until you truly engage with them.”

Conversations that cook, not burn

Early in the course, journalist and author Mónica Guzmán sparked a thoughtful discussion about the power of curiosity to preserve civility. In her interview with Taylor, she spoke of the personal pain of the political divide within her family: She’s a Democrat, and her parents support Donald Trump.

Conversations have gotten intense, she said, but the family has discovered ways to keep them at a simmer. “We welcome the heat. We’re in the heat,” said Guzmán. “But it feels like it’s cooking something — not burning something.”

In 2024, the stakes seemed higher than ever and learning how to have a respectful dialogue isn’t just about keeping the peace at the dinner table, Guzmán said. She believes it’s the key to holding our democratic republic together, noting that in these times, it’s essential to find tools and strategies to keep an open mind and hear other perspectives.

After watching her video and others that followed, the students shared their responses with each other in a full-class discussion board. “It was quite vulnerable knowing the whole class could read your reflection,” said Hillyard, who was impressed with the level of commitment and engagement. “Students were open and honest with each other.”

Closing the civility gap

What about the so-called red-blue political divide? The class addressed it head-on with a moderated conversation between two long-time legislators who have since left office: Derek Kilmer, former Democratic U.S. representative, and J.T. Wilcox, former Republican state representative, are long-time colleagues and friends.

In a video, they spoke of the threats they see to the country, including many legislators’ eagerness to fight simply for the sake of a fight. This behavior is increasingly common today and is “tearing down the institutions that have made our life in the United States possible,” Wilcox said.

Part of Kilmer’s advice on how to close the civility gap is to never overlook the power of seating arrangements. A few years ago, he set out to ensure a congressional committee he led was functional. When the group held hearings, he disrupted the party-line seating that’s typical in Congress. Instead, Republicans and Democrats intermingled at round tables, putting their heads together as the hearing unfolded.

“If you want things to work differently,” Kilmer said, “you have to do things differently.”

The role models for respectful dialogue in the class took other forms as well, Hillyard said. Dr. Karam Dana, professor in the School of IAS, and local rabbi Will Berkovitz, for example, recorded separate interviews to share their perspectives on the war in Palestine and Israel.

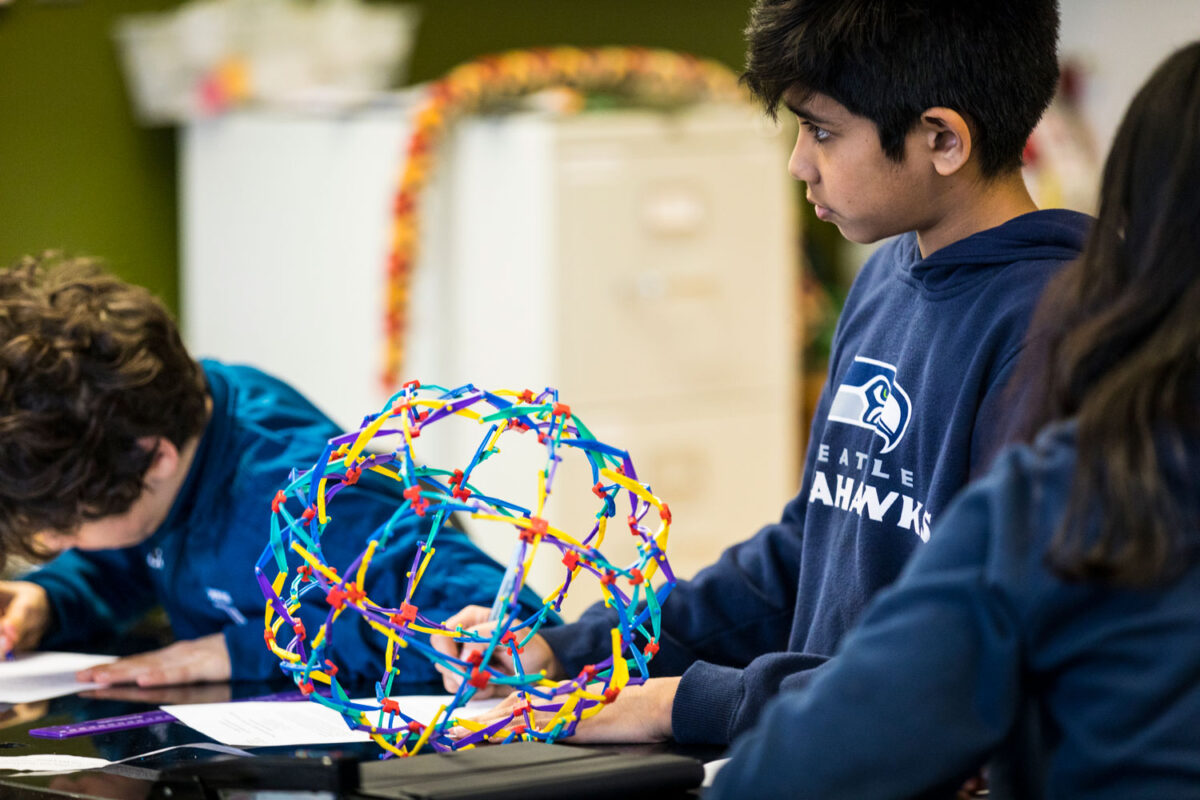

Over the course of the quarter, the UW Bothell students in the class also met in person four times to practice concepts they were learning online.

“It’s personally important for me that we create spaces so everybody who comes to UW Bothell feels safe to share what they’re thinking.”

Dr. Cinnamon Hillyard, associate vice chancellor for Student Success

Students tackle tough topics in real time

The Student Diversity Center facilitated small-group meetings for the class, offering a clear structure, ground rules and timelines to guide the dialogue (as opposed to debate). Students split into groups of three or four and were invited to share their stories by responding to the question, “What’s something that’s important to you?”

Rather than defend themselves, each person had the space to explain how they had come to hold a particular belief. “I was amazed how, even though [students] barely knew each other, they’d immediately engage in really tough conversations,” said Hillyard.

One student discussed the value he places on gun ownership and his dissatisfaction with recent Washington gun legislation. Another voiced opposition to vaccinations, sharing relief that they are no longer required for UW enrollment. A third person, whose father refuses to get needed counseling, spoke about the state of men’s mental health.

Statia recalled that he took a big risk when he revealed that, in the past, he had looked askance at the LGBTQ+ community. His attitude had grown out of some negative interactions in high school, but he’s since made a 180-degree shift and now considers himself a strong ally of the community.

Upon hearing each other’s stories, fellow group members simply asked follow-up questions. No one attacked or turned sardonic or rolled their eyes. “It was modeling what good dialogue looks like,” said Statia, “but equally important, what good listening looks like. It’s important to learn how to … bluntly… shut up.”

Reason for hope

Hillyard thinks the class met its goal of promoting civil dialogue. Students told her that they felt safe to freely express opinions that might not be so welcome in other classes. “In order to learn, you have to feel safe,” she said.

Taylor was also encouraged and inspired by how students practiced the skill of getting to know one another. “You are a generation of students that will face really important and powerful issues,” he told them in a wrap-up video, “and the question will be: How did we comport ourselves during that time? Can we see the humanity in each other and can we find ourselves to a place of repair?”

For now, the 198 students in “2024: Dialogue, Disagreement and Democracy” may have started a quiet revolution on UW campuses, practicing empathy, bridge-building and the kind of civility that could sustain our democracy.