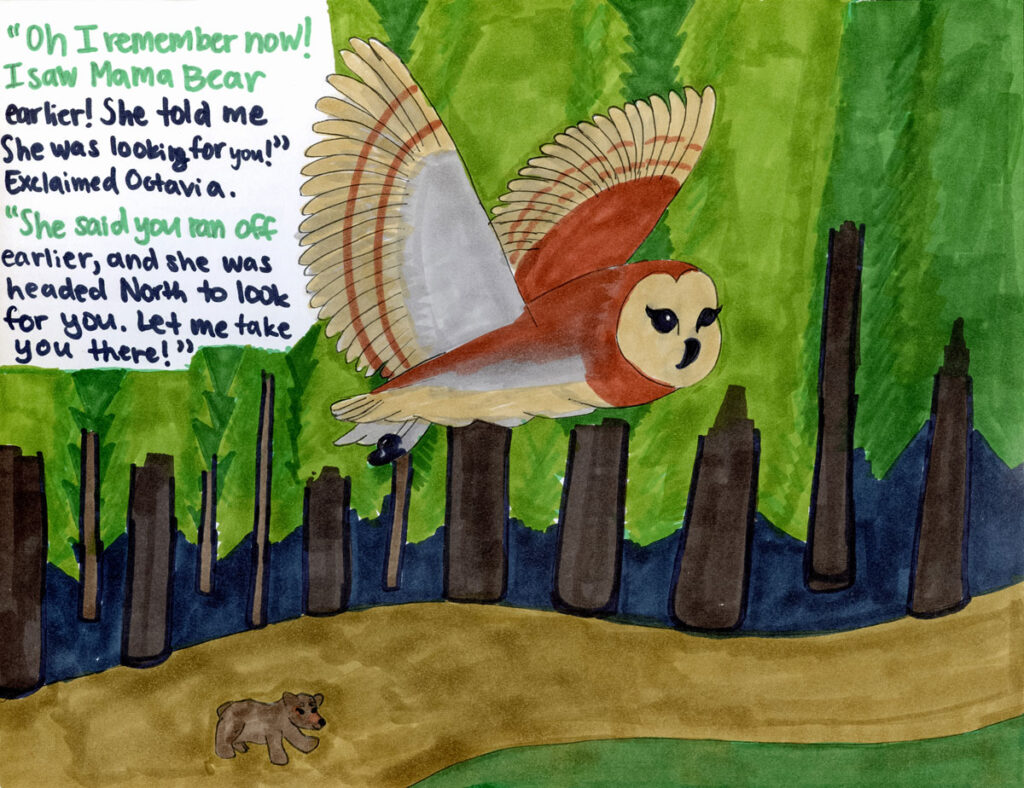

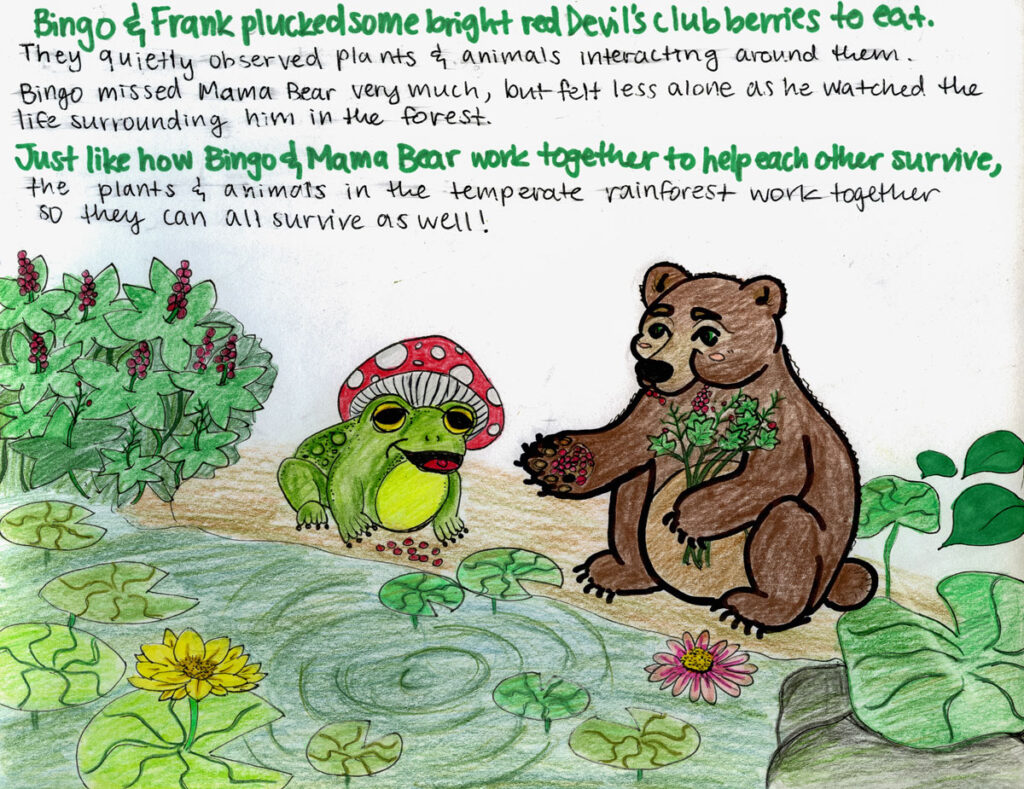

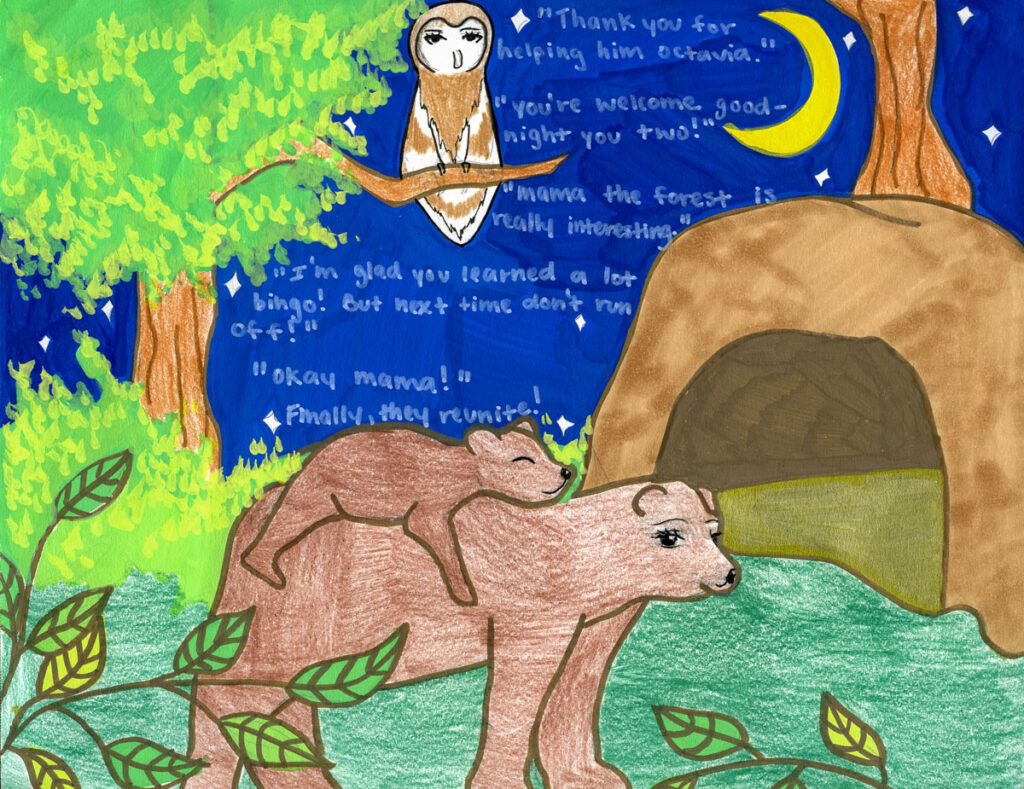

A bear named Bingo wanders the temperate rainforest of Cascadia, looking for his mother. As he moves through trees and along rivers and ponds, he encounters other local inhabitants: Olivia Owl, Frank the Frog and Seth the Slug, to name a few.

In this children’s book — authored and hand-illustrated by students in UW Bothell’s “Learning Ecology Through Storytelling” class — the emphasis is on interconnectedness and perseverance.

Bingo’s journey unfolded in one of six different books created by first-year and transfer students in the new Discovery Core offering. The course surveyed both children’s and scientific literature to explore ecology — and to inspire a deeper sense of connection with the planet.

Highly cross-disciplinary, the class was co-taught by Dr. Jennifer Atkinson, teaching professor in the School of Interdisciplinary Arts & Sciences, and Dr. Cynthia Chang, associate professor in the School of STEM.

Where science and narrative meet

Chang, a plant ecologist who studies Mt. St. Helens, rediscovered children’s books during the pandemic lockdown, reading for hours every day to her young daughter. “I was really struck by how creative and elegant really good children’s books are for teaching young kids about really complicated things,” she said.

She found picture books that tackled sophisticated topics ranging from emotions to morality, complex math to coding. Impressed, Chang had a thought: “Science communications could learn a lot from storytelling.”

Meanwhile, Atkinson, a humanities scholar whose work centers on environmental communications, was searching for a better way to talk to children about the climate crisis. Her ongoing investigations into climate anxiety had revealed a troubling trend: A deep sense of despair and hopelessness in young people who felt like they were born on the cusp of doomsday.

“How do we talk about the natural world in ways that inspire wonder and curiosity and connection as opposed to fear and despair?” Atkinson wondered.

With an Indigenous perspective

Chang approached Atkinson about a collaboration, and together they created “Learning Ecology Through Storytelling.” On their syllabus are children’s books such as “You Are Stardust” by Elin Kelsey and the “Mother Sockeye” series by Hetxw’ms Gyetxw (also known as Brett Huson), along with writings from Indigenous scientists including Drs. Robin Wall Kimmerer and Jennifer Grenz.

An Indigenous perspective deeply informed the course, which leaned into the interrelatedness of natural systems and the organisms that call them home. “Indigenous presenters and thinkers see the natural world as relations,” said Atkinson. “Kids are open to this. They intuitively see plants and animals as peers and friends.”

The emphasis on strong Indigenous voices motivated Aaliyah Chappell to enroll in the class. Her heritage includes the Cowlitz, Nisqually and Yakama tribes, and she was eager to explore her Native culture through stories and science. For her group’s book about the Salish Sea, Chappell constructed three-dimensional cutouts, including a Coast Salish-style orca whale.

Insights into children’s book publishing

How to craft a vivid story for children? The students gained priceless professional advice from a series of guest presenters. Gyetxw (Huson) and Kelsey visited the class via Zoom, followed by illustrator Soyeon Kim. “They brought insights into how much work it takes to write a seemingly short, simple children’s book,” said Chang.

Students saw firsthand the drastic revisions that are often part of the process. Kelsey’s “You Are Stardust,” for instance, began as a 100-page treatise on the interconnectedness of species. In its published form, the book is about 13 pages long, with spare, elegant text that skims across Kim’s whimsical artwork.

During her presentation, Kim spotlighted the dioramas that illustrate “You Are Stardust” and other books. In creating them, she sometimes uses Kelsey’s discarded text to inspire her images. Student Skyler MacPhee was especially taken with the dioramas, finding Kim “really inspiring to listen to.”

Most students expressed surprise at the difficulty of writing an effective children’s story. “It’s one thing to understand the material and the science,” said Atkinson. “But to explain it in a way that’s clear and entertaining for children … that’s really hard to do.”

“How do we talk about the natural world in ways that inspire wonder and curiosity and connection as opposed to fear and despair?”

Dr. Jennifer Atkinson, teaching professor in the School of IAS

Forays into the forest

To animate the ecological interactions that sustain our world, many sessions of “Learning Ecology Through Storytelling” gathered students together in the Environmental Education & Research Center, a facility six miles from campus in Saint Edward State Park that is home to UW Bothell’s Collaborative for Socio-Ecological Engagement.

One early exercise sent students on a self-guided tour through the surrounding forest. Their assignment: Invent words to describe what they saw. Indoors, the idea made little sense to the students, Atkinson said, and “there were a lot of cocked heads and knitted brows.”

But the forest brought the assignment to life. Perhaps inspired by famous children’s book, “The Lorax,” or calling on childhood memories of outdoor play, the students delivered “creative, fun, funny responses — but stayed faithful to scientific concepts,” said Atkinson.

Connecting with young learners

The off-campus location also proved a great platform to interact with the community, said Chang. After seeing students from the nearby Heartwood Outdoor School pursuing lessons in the park, she approached the school administrators: Would their young pupils attend a presentation by UW Bothell students debuting their children’s books?

In the final week of classes, students aged 4-11 visited the EERC, delving into Cascadia ecosystems as they met Bingo the Bear, watched Chapell and her Salish Coast orca, and laughed to see a crab catch a ride on a jellyfish.

“The proof was in the pudding,” said Atkinson, recalling young learners on the edge of their seats, hands raised high with questions.

Shifting the traditional narrative

The source text for students’ creations was the “Cascadia Field Guide,” which devotes each of its chapters to a different ecosystem in the Pacific Northwest. With its focus on inter-species relationships, the book also conveys an Indigenous perspective. “It makes intuitively more sense than a traditional plant identification guide,” Chang noted.

Students formed groups based on the ecosystems they most resonated with — temperate rainforest, outer coast, Salish Sea or tidewater glacier — and began drafting stories.

According to Atkinson, in the beginning the narratives were filled with overwhelming scenes of oil spills and dead animals. But she watched that tone shift dramatically over the course of the quarter. Instead of doom and gloom, Atkinson said, students began to see that “solutions exist, and we can contribute. You’re not alone in caring; others care, too.”

Class leaves lasting impact

The students report that their sense of connection to the natural world also evolved. Erick Hernandez admitted he had “never been much into the environment” before enrolling in the class.

“The class made me pay a lot more attention to things I previously overlooked and start caring about things more,” he said. By the end of the quarter, Hernandez was planning to volunteer with a community cleanup effort.

Chapell, who crafted the Salish Sea orca, had some revelations of her own. “The climate crisis and the state of the environment is serious compared to what I thought before,” she said. “If you don’t care about it, you don’t care about your own survival.” She intends to weave her Indigenous culture into her Computer Engineering major.

As for Atkinson and Chang, they’ll offer the class again. They remain committed to inspiring a sense of hope and agency in both local preschoolers and UW undergraduate students.

“These are resilient ecosystems,” Chang said. “We are part of them! By virtue of your caring, you will help make a difference.”

Pages from “Bingo the Bear” by Mikala Anderson, Alisa Darskaya, Patricia Lucas, Skyler MacPhee, Jennifer Nguyen and Aasha Steele.