Students in the University of Washington Bothell’s School of Educational Studies spend countless hours learning how best to educate young minds and foster them to bright futures.

Many students, such as alumna Adrienne Minnery (M.Ed. ’10), also already have teaching experience when they come back to school in pursuit of a master’s degree or other continuing education. Teaching and learning are an ongoing process, she said, and this belief is at the center of her work as both an educator in the Shelton School District and as a researcher.

After graduating in 2010, Minnery began to think not only about how to better teach in her own classroom but also about where there was opportunity for growth in traditional teaching methodologies. Years later, she then reconnected with Dr. Antony Smith, associate professor in SES, and their discussions planted the seeds of collaboration and innovation that led them to do research into a new teaching method.

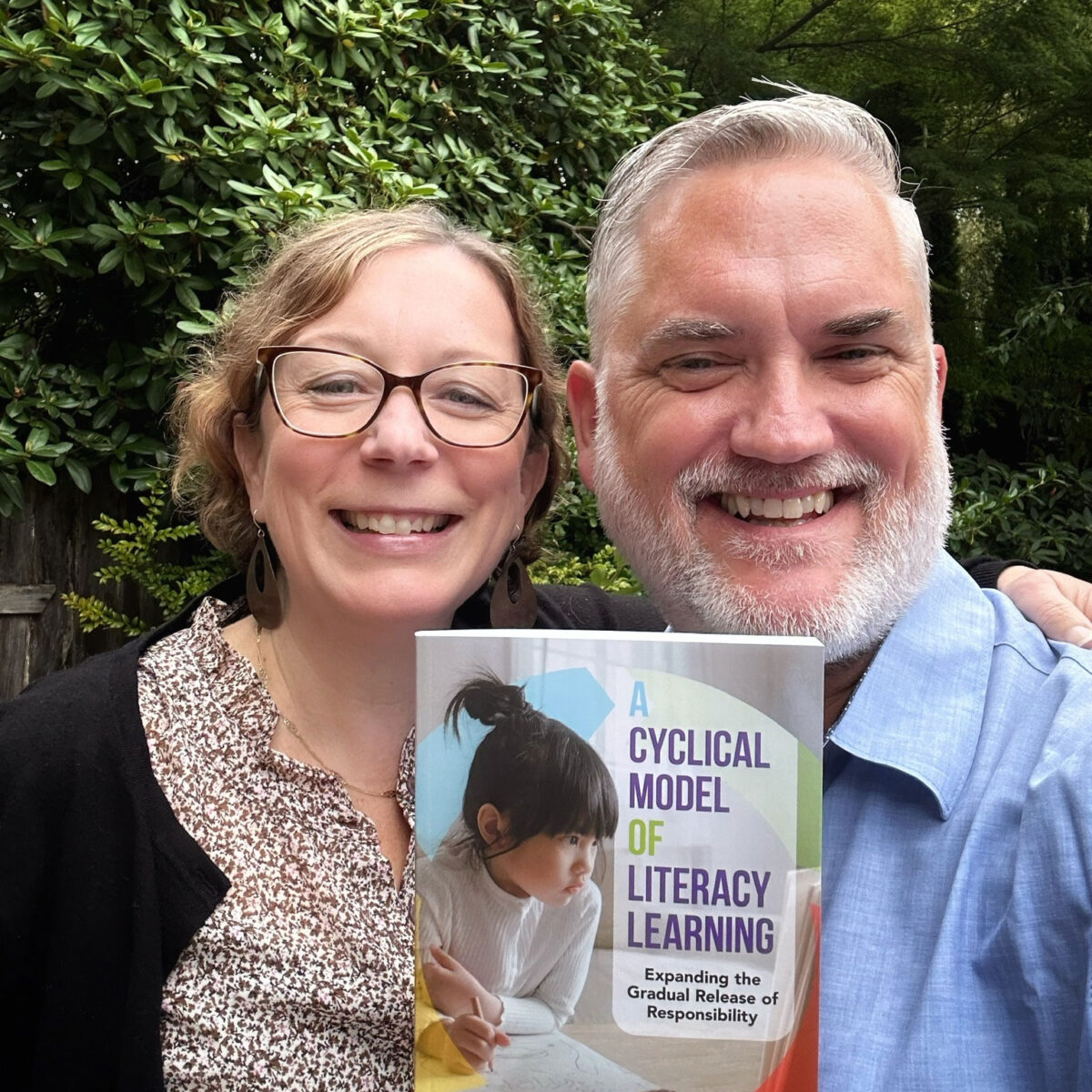

Little did they know having that first cup of coffee that their work would also culminate in the publication of their co-authored book, “A Cyclical Model of Literacy Learning: Expanding the Gradual Release of Responsibility,” which they published in September 2024.

“My research has always been grounded in schools and working with practitioners,” Smith said. “To collaborate as co-authors in this research with a former student has been a welcome extension to that. Together, we’ve developed her ideas in classroom settings and anchored them in the academic sphere, and that felt really good.”

Reimagining early literacy education

What began as a resource for Minnery to use in her own classroom soon became the foundation for a collaborative research project. Through Minnery’s experiences in the classroom and Smith’s research, the pair identified that a traditional teaching and learning model known as the gradual release of responsibility, or GRR, seemed to be missing some key elements.

“Something I realized right away in developing a new model was that the old model focused on task completion as the goal,” Minnery said. “But I started to question: What about the responsibility for learning in the model?

“In thinking about early literacy, there’s so much work that the learners are taking on to become readers. Once you reframe the model to include the learner,” she said, “you have to look at all the things that are happening internally for them and what motivates them.”

In the old method, the responsibility shifts from the teacher slowly to the student. But this model doesn’t fit early learning very well, Smith said, particularly as it applies to literacy education. “And so, our new model not only emphasizes constructing knowledge together but is also cyclical rather than linear because we know that learning is continual.”

Smith and Minnery hoped to create a literacy process that accurately reflects the energetic and complex world of classrooms. Looking specifically at reading, writing and word study in the primary grades, the pair identified five key motivators for learning: challenge, creativity, collaboration, choice and independence.

“The model also encapsulates a trusting relationship between teacher and student which you build by including the learner as a whole child within the model,” Minnery said.

Field testing a new model

Historically, Smith noted, aspects of learning that can’t always be quantified in metrics, such as engagement and motivation, have been largely left out of literacy research.

“When we think about challenge, creativity, collaboration, choice and independence, those are all the kinds of things that make us want to learn,” Smith said. “And those are not only absent from the GRR, but they’re also largely absent from literacy research. Motivation and engagement, for example, have long been known to be powerful factors in learning anything but especially in learning to read.”

With a grant from the Washington Educational Research Association, Smith and Minnery began to test their model in other classrooms — branching out to seven first-grade classrooms across three schools in the Seattle area. The teachers learned the new method, and students took standardized reading tests before and after the new curriculum was implemented. The study looked at both qualitative and quantitative results, including tests as well as classroom observations.

Smith and Minnery saw positive results in the early part of the study and published their findings in the peer-viewed journal, The Reading Teacher. Then, fueled by that success, they looked to expand on their research and began working on a book in 2020.

“This idea really started small, as a resource for my classroom, and then just kept building,” Minnery said. “We both started to see that there were deeper underlying patterns that then led to the development of the model and then a book. It’s been quite the path that we’ve taken together as we’ve gone through different cycles and iterations.

“On the whole, it’s a much broader approach to thinking about literacy learning.”

Rising to comprehension challenges

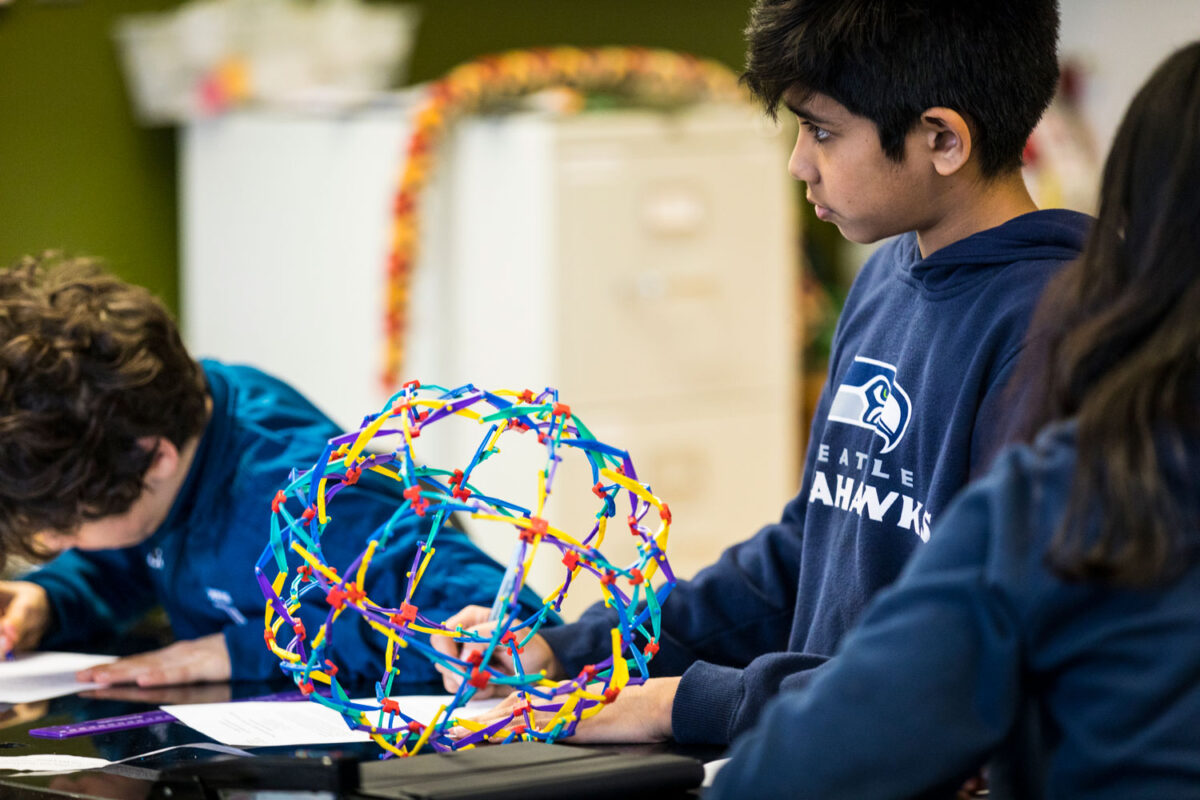

Students are often given texts that are in alignment with their current reading level. In their research and experience, however, Smith and Minnery found that providing text beyond that perceived level can be a far more effective tool. Many of the study’s teacher participants stated that the challenge proved to be one of the most powerful drivers.

“It’s often the motivator that young children especially are prevented from accessing,” Minnery said. “But what we found in feedback from other teachers — and what I’ve seen in my own classroom — is that when experiences are structured to provide a challenge for students, teachers are surprised by the growth they see in their students. They’re able to rise to those challenges.”

This idea of challenge, Smith added, was drawn in part from math education and the concept of “productive struggle.” In the study, teachers used close reading, a method of analyzing text in detail, to introduce more complex texts. Students were invited to use context clues and decode the meaning similar to how one might solve a math problem.

“Students are allowed to struggle with a complex concept, as long as the teacher provides support to avoid frustration or absolute failure,” Smith said. “If they have the right, patient support to help them stick with it, they come through more motivated to learn and also with more knowledge.”

Minnery recalls seeing how impactful this method can be in her own classroom with a student who learned English as a second language. By reading poetry instead of prose, the student was able to gain a new understanding of certain words and patterns in English.

Since embarking on this research, Minnery has taken on a new role as director of curriculum development and instruction for K6 in the Shelton School District, where she continues working to advance literacy learning in the classroom.

Teaching children, not curriculum

In their new book, the authors include vignettes to illustrate the model’s ideas in practice. The book also includes a foreword by P. David Pearson, the originator of the GRR model, where he acknowledges the cyclical model as a necessary evolution for literacy teaching and learning.

“I always tell my students at UW Bothell who are becoming teachers that ‘your job is not to teach curriculum, your job is to teach children,’” Smith said. “Teaching is a complex endeavor, and we need to think broadly about what it means to be in this enterprise of education, because it’s complex and rich and exciting. I hope this book will shape the field.”

Just as their model for teaching and learning is cyclical, the pair’s work is still ongoing as they continue to evolve and iterate their methods. Their next step will be presenting the book at conferences and working to get the model into more schools.