As the effects of climate change continue to disrupt entire ecosystems and the animals that depend on them, monitoring the earth’s most vulnerable species is more important than ever. Among the endangered and threatened species native to the Pacific Northwest, there is perhaps none more emblematic of the region than the Southern Resident killer whale.

Another local orca species, the Bigg’s killer whale, eats a diet of marine mammals — but the Southern Resident killer whales (also known to many as the J, K, and L pods) primarily eat Chinook salmon, a once bountiful fish that was listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act in 1999.

The Southern Resident killer whale joined the Chinook salmon as a protected species in 2005, when it was listed as endangered.

Both orcas and salmon are considered keystone species, meaning they are vital to the health of their marine ecosystem. For scientists like Dr. Shima Abadi, an oceanographer and associate professor at the University of Washington Bothell’s School of STEM with a joint appointment at UW’s School of Oceanography, protecting these animals is a top priority.

While food scarcity is one concern for Southern Resident killer whales, Abadi’s latest research aims to help mitigate another common threat to orcas — maritime traffic.

To solve this problem, Abadi and her team must first gain a better understanding of how vessel traffic impacts orca movements and behaviors. So to support orca monitoring at the University of Washington, the Paul G. Allen Family Foundation recently committed a grant of $1.5 million to the College of the Environment for more innovative research.

A novel approach to monitoring

Orcas spend almost all their time below the water’s surface, often coming up only when they need to breathe. Because of this, Abadi said, it’s difficult to get a full picture of their movements from visual observation alone.

“Even if you’re looking underwater, visibility is limited, making sound the primary tool for probing the ocean,” Abadi said. “Light dissipate so fast, but sound can propagate thousands of kilometers so we can learn and communicate underwater through sound.”

Abadi has spent most of her career researching acoustical oceanography, investigating sound sources ranging from ambient noise in the ocean and seismic shifts in the ocean floor to the calls of marine mammals and the impact of noise pollution from vehicle traffic on fish.

In her latest work, Abadi and a team of four co-researchers are using a novel sensing technology called Distributed Acoustic Sensing to monitor killer whales in Puget Sound. The co-primary investigators in the project include Dr. William Wilcock (UW School of Oceanography), Dr. Brad Lipovsky and Dr. Marine Denolle (UW Earth and Space Sciences Department) and Dr. Scott Veirs from the nonprofit organization Beam Reach.

Where similar research in the past relied on hydrophones, which pick up sounds at a singular point, DAS transforms fiber optic cables into receiver arrays that can pick up sounds along the full length of the cable. DAS has previously been used to detect seismic activity, but in the last several years it’s been proven successful at detecting marine mammals.

“This innovative approach could be a breakthrough in conservation efforts and potentially have a significant impact on protecting our orcas from the effects of maritime traffic,” Abadi said.

“This innovative approach could be a breakthrough in conservation efforts and potentially have a significant impact on protecting our orcas from the effects of maritime traffic.”

Dr. Shima Abadi, associate professor, School of STEM

The science of sound

With the grant, Abadi and her fellow researchers will be monitoring fiber optic cables near Whidbey Island and San Juan Island for Southern Resident killer whales over a two-year period.

“The Paul G. Allen Family Foundation is excited to support fresh and powerful approaches like Distributed Acoustic Sensing to understand and protect vulnerable species, especially here in the Puget Sound,” said Gabriel Miller, the foundation’s director of technology. “Through a better understanding of behaviors and threats, we can deploy more efficient and effective conservation practices.”

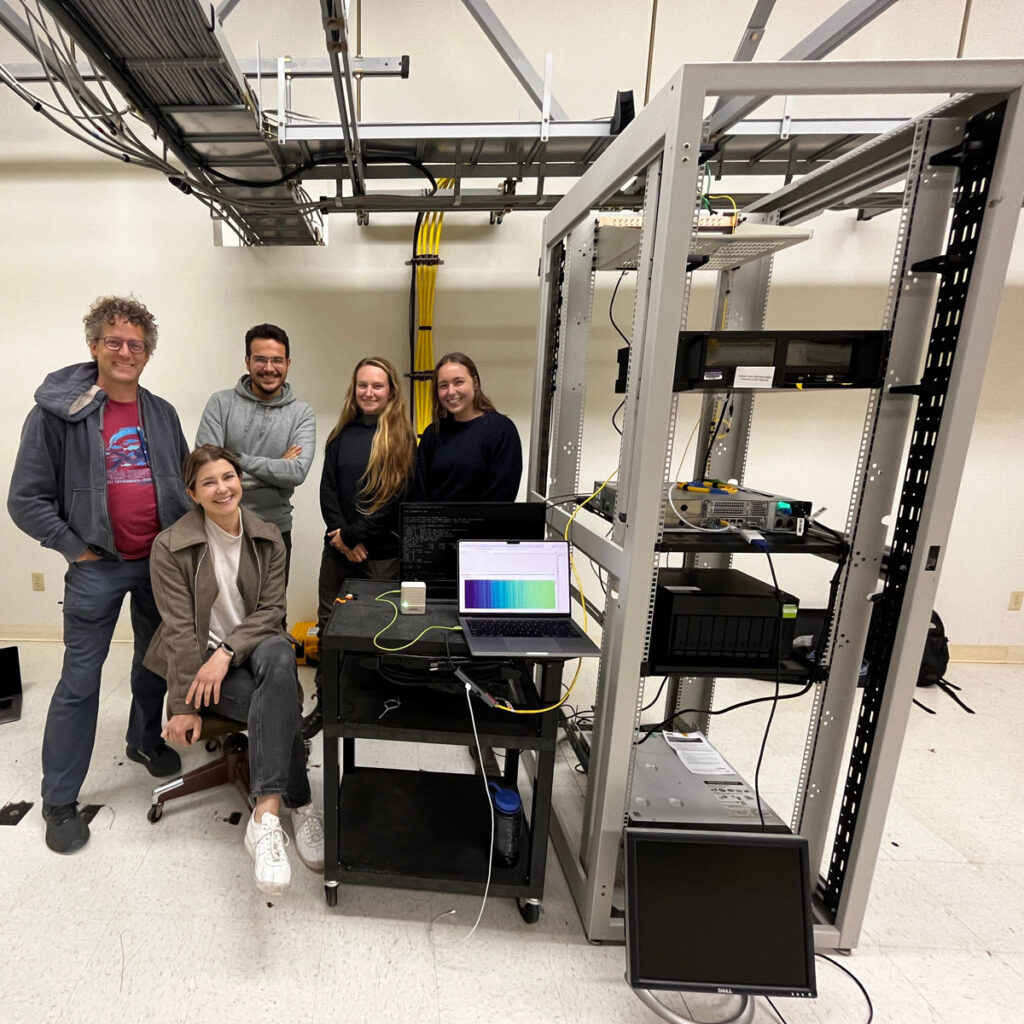

The project kicked off in October 2024 when the team added a DAS device to an existing fiber optic cable so that it could record bioacoustics. Additional cables will be deployed in 2025. The principal investigators, along with graduate students, will then analyze the data gathered throughout the project period.

“My primary goal is to help find and implement solutions that can mitigate negative anthropogenic impacts on marine mammals,” said Samantha Juber, a doctoral Oceanography student at the UW. “I think that DAS could play an invaluable role in this. Better understanding how DAS works and how to better implement it will help me work towards this goal. The skills that I will develop in the process — including big data management, signal processing and critical thinking — will help me wherever I go.”

The students contribute to the project in a number of ways, from the logistics of setting up field work to analyzing data to look for killer whale calls. As DAS was previously used for recording low frequency sounds such as seismic shifts, the research team also continues to work on optimizing the equipment to record higher frequency sounds.

“Distributed acoustic sensing has the potential to create a global monitoring network for cetaceans and help protect endangered or threatened species,” Juber said. “The research we are doing now is crucial in understanding how we can apply this recording technique to a broader range of species.”

As it analyzes the data, the team is also doing “ground truthing” to confirm new readings. Hydrophones have been proven successful at capturing whale calls, so the researchers are comparing data from hydrophones with data from the DAS technology to help confirm the presence of orcas.

A network of discovery

In partnership with Beam Reach, a local nonprofit organization that runs a network of visual and acoustic observations in Puget Sound, the research team has access to several hydrophones — as well as bioacoustics experts Dr. Val Veirs and Dr. Scott Veirs, the father and son duo who started the nonprofit.

Beam Reach supports the project by providing important comparative data from their hydrophone network. The organizations connections in the broader orca-watching community have also proved invaluable, Abadi noted. The Veirses stay plugged into the Orcasound network to let the team know when and where orcas have been found near the hydrophones and the fiber optic cables. Even with a vast network of both professional and citizen scientists, however, tracking the orcas can prove challenging.

“During the day, visually we have a wonderful community of sighting networks around Puget Sound, and even on bad weather days people get out there on bluffs with binoculars. It’s helpful because, although killer whales are very chatty, about a third of their waking hours they’re not making any sound,” said Scott Veirs (M.A. ’97 and Ph.D. ’03, both in Oceanography from the UW). “Through sightings and the hydrophones, we can help direct attention to the right areas.”

Veirs said he is excited to be a part of the DAS project as he hopes it will help expand the capabilities of acoustic monitoring and allow for capturing sound in more areas without the limits of hydrophone placement.

Isabelle Brandicourt, a doctoral student in Physical Oceanography at the UW, is also interested in DAS as a more sustainable option for passive acoustic monitoring that takes advantage of existing infrastructure.

“I have a background in electrical engineering, but I have always been very passionate about the ocean and ocean science. In an effort to combine these two sides of myself, I found the world of acoustics,” Brandicourt said. “Using passive acoustics to measure ocean metrics is noninvasive and can tell us so much more than other observation systems such as visual surveying.

“DAS could expand the field exponentially,” she added, “and decrease the amount of technology that humans have to put in the ocean and potentially lose in the name of research.”

A need to share the ocean

In all her projects, students are integral to Abadi’s work. She brings both undergraduate and graduate students together in her research, she said, and many of her undergraduate students go on to do graduate and postdoctoral work with her after getting a taste for the research track.

“Students are a key part of this project, doing the actual on the groundwork, and it’s fun to see our different programs across UW interacting with each other and to see students learning from one another,” Abadi said. “I’ve always involved students in my work, and it’s great to see them come from different backgrounds and be exposed to new possibilities.”

As the project continues, she added, opportunities will open up in 2025 for undergraduate students to join in the data analysis and sea-going experiments.

Meanwhile, over the next two years, the team hopes the DAS data they gather will provide new insights into how orcas are affected by maritime traffic. While there have been some state and regional initiatives to help curb vessel speed and prevent collisions, Abadi noted that more can be done to help protect this keystone species.

“This technology opens new possibilities for us to expand our analysis on a much larger temporal and spatial scale,” Abadi said. “We hope to show that fiber optic cables can detect Southern Resident killer whale vocalizations, enabling us to use these sounds to triangulate their locations and better track them, allowing vessels to be warned to reduce their speed or avoid the area.”