With a doctorate in pathobiology, Stefanie Iverson Cabral has been teaching courses in microbiology, infectious diseases and global health since 2015 in the School of Nursing & Health Studies, always taking any opportunity to share her historical interest in quarantines.

This school year, she decided to make Quarantine and Isolation its own 200-level, spring quarter course to help students explore the policies, ethical considerations and potential abuses in managing outbreaks.

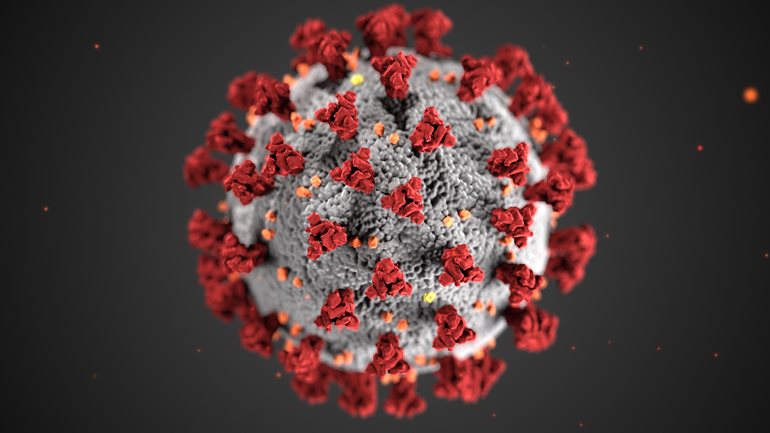

Then, the coronavirus and the COVID-19 outbreak broke through the classroom door.

History lessons made real

“It’s a little bit ironic that our quarantine class isn’t being taught in person,” she said. “I’m going to have to revamp it in light of the real-time current events. I will be having students do a lot of comparing/contrasting this current event with situations from the past.”

Iverson Cabral always thought it strange when people downplayed the seasonal flu. “Flu makes me very nervous. People underestimate it,” she said.

When she talked with students about the 1918 flu that killed more than 50 million people worldwide, she would ask what they thought about a future pandemic.

“Are we ready as a society, and will it be as bad?” she would say. “And most students were like, ‘Nope, it’s not going to be as bad; it’s not going to happen.’”

Recently, a previous student emailed her. “Remember when you asked us how we would respond? We’re seeing it!”

Iverson Cabral said, “I couldn’t predict it would be this particular virus, but it was inevitable.”

Battling the outbreak

SARS, MERS, Ebola and swine flu concerned Iverson Cabral, but she’s more worried now because the new coronavirus is apparently spread by some people who show no symptoms.

“A lot of people have this and don’t know. It promotes a much wider spread than we had with those other diseases,” she said. “That’s why it makes sense, in my opinion, to be shutting things down.”

While laboratories around the world are working as fast as they can to develop treatments and a vaccine, those are months away at best, she said. Meanwhile, more testing can help track and control the spread of COVID-19.

“When you don’t have a vaccine and you don’t have a cure, testing is really our best bet,” Iverson Cabral said. “Lack of data is one of the things that really bothers me. Ideally, we’d be able to test everybody.”

She’s also concerned about the mental well-being of students and the public at large. Reports are on the rise that some people are blaming the pandemic on marginalized communities, as she has seen in history as recently as the 2003 SARS virus.

“It could be minor, with people making jokes,” she says, “but it plays to some underlying xenophobia. This is a virus. It doesn’t care who you are.”

Fighting a virus with information

Because of her expertise, Iverson Cabral has been asked a lot of questions by students and others on and off campus. In response, she has created a website with information about the coronavirus, updated daily.

The site includes a chart that illustrates the value of social distancing in the different responses of two cities during the 1918 flu. Toward the end of World War I, the city of St. Louis closed down schools, churches and theaters. The city of Philadelphia went ahead with a war bonds parade, which was soon followed by significant loss of life in the City of Brotherly Love. Deaths were more moderated in St. Louis.

The chart shows the value of “flattening the curve” to prevent a peak of patients that would overwhelm hospitals, she said.

“I think there are people who don’t appreciate this is as severe as it is,” Iverson Cabral said. “Social distancing can really help stop the spread.”

Taking it seriously

People are resilient and have survived pandemics in the past, says Iverson Cabral. But it’s no longer an abstraction. Her students will have lived it.

“Now, we will study how we handled this,” she says. “Did we do a good job? Could we do better and try to learn for the next time?”

“Most importantly, how can we critically evaluate how scientists, government and society responded so that when we come out of this — when we make it to the other side of the pandemic — we are better prepared for the future?”