Since the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s, people of color have entered higher education and professions, settings previously occupied almost exclusively by white people. Many schools and workplaces and universities, however, continue to lack diversity.

“Growing up, for example, I absolutely loved science, specifically chemistry,” said Alex Margarito, a 2019 alumnus of UW Bothell’s School of STEM. “But I never considered it as a career because I had believed that STEM fields were reserved only for white people — and that was largely because I only ever had white professors.

“When you don’t see people who look like you in certain spaces, you tend to think it’s because people like you don’t belong there,” he said.

That perception began to change after he entered higher education, first at Cascadia College and then UW Bothell, two institutions on a shared campus that is known for its diversity. At UW Bothell, for example, approximately 60% of students identify as people of color.

Both as a college graduate and as a high school teacher now, Margarito knows from firsthand experience that receiving an education in a diverse environment can make a profound impact.

Opening parameters of possibility

According to the National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics, 77% of elementary and secondary science and engineering educators are white. “Because I had never seen a teacher of color, I assumed that people like me didn’t go on to become teachers, that just wasn’t the work we did,” said Margarito. “It never crossed my mind as a possibility.”

So instead of pursuing a career in chemistry, after graduating from high school Margarito started working at Target. “I wasn’t in the best place. I was hanging with the wrong crowd and getting into trouble,” he said. “I really had no outlook on my life.”

There he met the woman who would become his wife — the person who pushed him to go back to college and “completely changed my life and made me who I am today,” he said.

In 2014, three years after graduating from high school, Margarito started his journey in higher education at Cascadia College. At that point, however, he still was not planning on a career in STEM.

“It wasn’t until a few quarters passed that I started considering it,” he said, “because then I had been taught by multiple professors who looked like me. That was what ultimately gave me the confidence to enroll in science courses and pursue my passion for chemistry.”

Pursuing a career in chemistry

Margarito finished his two-year program at Cascadia in 2017 and then enrolled at UW Bothell, where he met Dr. Dan Jaffe, a professor in the School of STEM.

Margarito took atmospheric chemistry with Jaffe his first year at the University. Jaffe was so impressed with Margarito’s performance that he offered him a job as a research assistant. “Alex was a strong student and energetic in our research lab. He did some very interesting research with the city of Seattle on indoor air pollution,” Jaffe said. “And everyone on my team found him to be a fun student to work with.”

The pollution research was in response to wildfires in summer 2019. “I monitored air quality and analyzed the data as part of a city pilot project to offer residents a fresh air oasis at some community centers,” Margarito said. “The two years prior — 2017 and 2018 — had been the worst years on record in the West. My research hopefully helped give the city better information about health risks, monitoring equipment and the benefits of enhanced filtering.”

Margarito and his work made an impression on staff at the city and helped lead to a job offer from Seattle’s Department of Parks & Recreation.

“That was my first job out of college, and I wouldn’t have gotten it without Dr. Jaffe,” Margarito said. “He made a really big impact on my life and gave me confidence to pursue a career in STEM.”

Coming full circle in education

After receiving his bachelor’s degree in Chemistry, Margarito went on to also get a Master of Education degree at the Seattle campus of the University of Washington. And with that accomplishment, he said, he can both work in chemistry — and make a difference for the next generation.

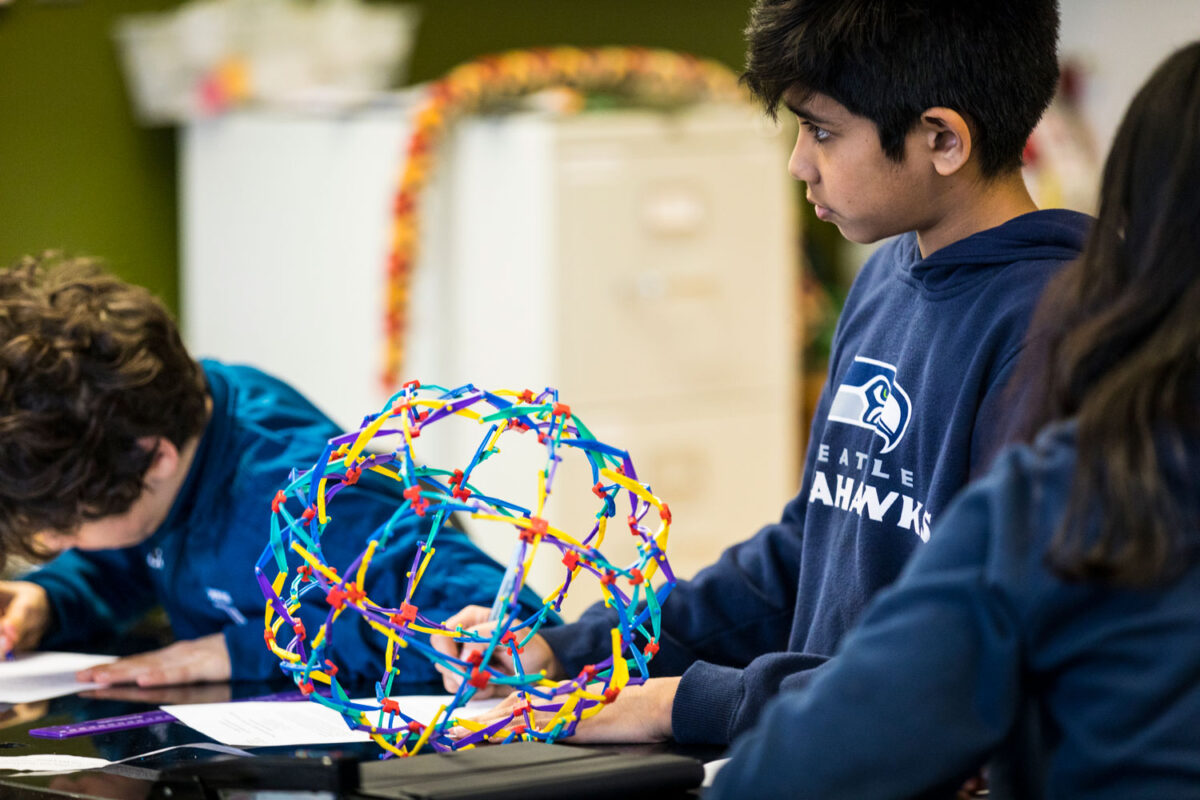

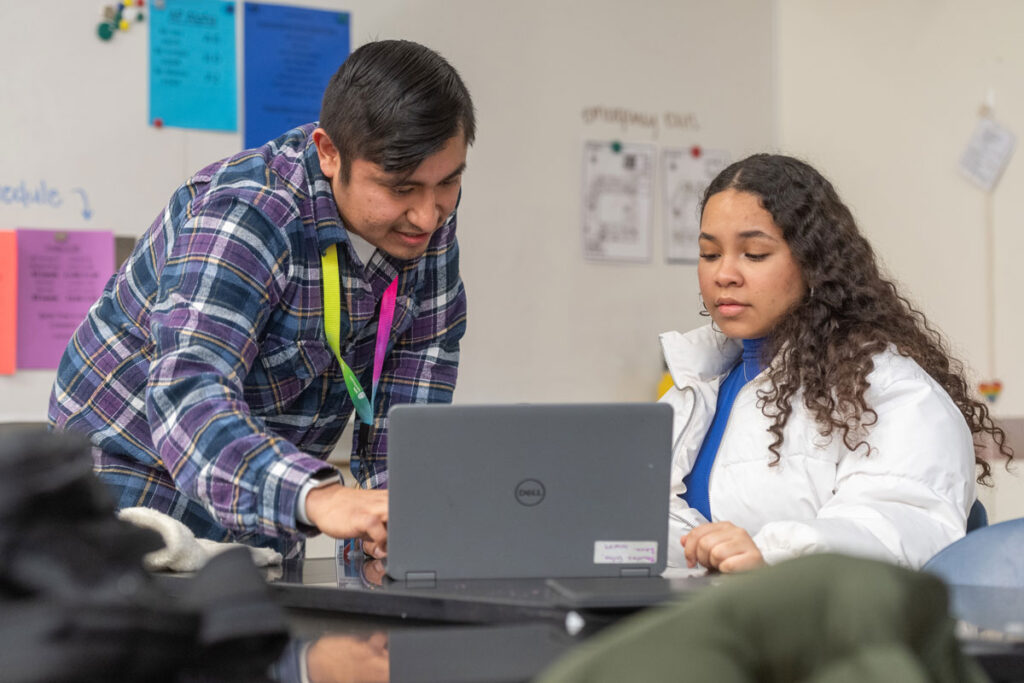

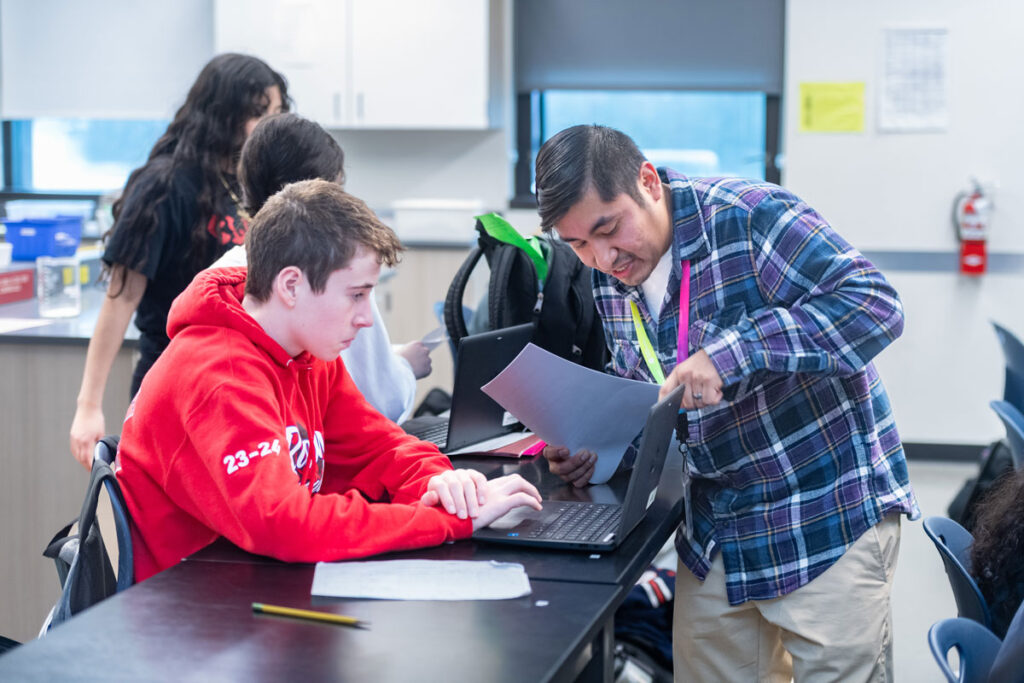

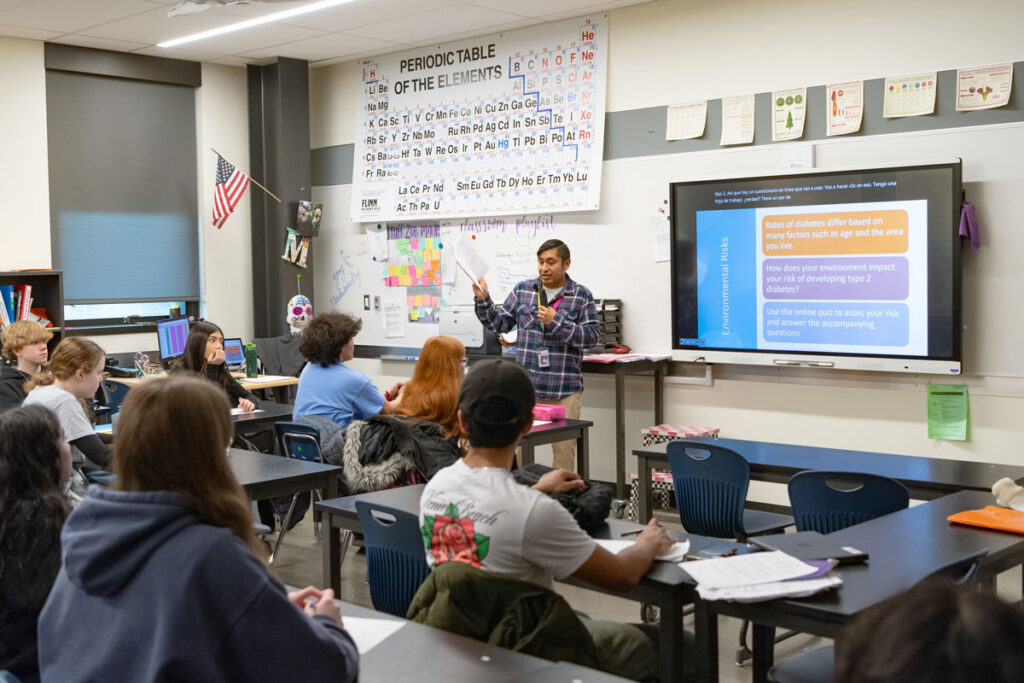

“I now teach chemistry at Juanita High School,” he said. “I am that teacher of color I never had, breaking down barriers and showing students like me that they do belong and can succeed in STEM careers.”

He said he does so, in part, by being open and honest with his students. “I don’t sugarcoat or hide anything from them,” he said. “I tell them that it will be hard, because it will be, but I also tell them they can achieve anything they set their mind to as long as they have the right resources, grit and perseverance.”

Having been a teacher for three years now, Margarito has witnessed firsthand the impact he is making.

“I have this one student whose family really struggles financially. The student told me that his parents tell him not to go to college and to just work because they need the money,” he said. “One day he told me straight up, ‘Mr. Margarito, you are the reason why I don’t want to do that. If you can do it, I can do it, too. You showed me that it’s possible.’

“To hear that directly from a student is powerful,” Margarito said. “I don’t have to wonder whether I am making a difference. I know that I am.”

I now teach chemistry at Juanita High School. I am that teacher of color I never had, breaking down barriers and showing students like me that they do belong and can succeed in STEM careers.

Alex Margarito, Chemistry ’19

Removing barriers to success

Margarito’s own background as a non-native English speaker also informs his approach to communicating with students, he said, recalling his experience in first grade when he was pulled aside for lessons in English as a second language.

“When we took our language and reading test at the end of the year, I went from not being able to speak the language to having the best reading score in the class,” he said.

Growing up, Margarito was taught that assimilating was a necessity for succeeding in life. Even his first name, Alex, is an Americanized version of his father’s name, Alejandro.

“All my life, my dad had been telling me to assimilate, to sound white and act white, so that I didn’t have to struggle the way that he did,” Margarito said. “That’s part of the reason why I pushed myself so hard to learn the language and to not have an accent.”

In his classroom, however, Margarito said he enjoys meeting students where they are and speaking conversationally with them — whether that means using slang and less formal ways of speaking that students from low-income areas might be more comfortable with or switching to speaking in Spanish.

Serving as a role model

“Now that I’m in a place where I’m in a position of authority and I’m a role model for these students,” Margarito said, “I really wanted to make it apparent that you can speak the way you want to speak and there’s nothing wrong with that.”

As part of the diverse Lake Washington School District, Juanita High School has a population of students who speak 59 different primary languages in their homes. At least eight languages are spoken among Margarito’s students.

To ensure his students are not left behind in any way because of language, Margarito provides assignments and other documents in multilingual formats whenever possible. He also enables a translation feature on his classroom smart board to provide Spanish subtitles as he speaks.

And while not all teachers do these things yet, he said, these practices are becoming common as educators seek new ways to make classrooms more inclusive.

Looking to the future of his own career, Margarito said he plans to one day teach at the college level.

Family tree grows new roots

“While I still have dreams of where I want go,” he said, “I think it’s important to also reflect on how far I have come.”

He explained that his parents are from a small town in Mexico that doesn’t have electricity. “My family came from nothing. My parents were living on the streets at seven years old, selling a variety of things to get by. They never graduated from elementary school, and despite now living in the U.S., neither one of them speaks English. They struggled a lot — but always dreamed of their kids getting a good education.

As a first-generation college graduate, Margarito can now look forward to a better future for his children, as well. “I am just happy that my family tree is never going to be the same from here on out,” he said. “My kids will always have an opportunity in life, something my parents never had.

“And I hope that by teaching at the high school level, I can shape the family trees of my students, too, and the generations to come.”